Grisly news keeps coming in from Russia about the activities of the Russian Federal Security Service—the FSB, which is descended from the KGB. In account after account, anarchists and anti-fascists describe how the FSB kidnapped them, planted weapons in their cars, and used torture to force them to sign false confessions admitting to participating in an obviously invented terror network.

Why should we care about the Russian torture cases, specifically? At first, it may strike people in the US and Western Europe as yet another abstract tragedy, just one more call for international solidarity with unfortunates in a faraway land. But the stakes here are much more significant. What is taking place in Russia is a nightmare scenario that could recur closer and closer to us if we don’t take it seriously.

For decades now, the security agencies of many different countries have repeatedly attempted to fabricate national and international “terrorist conspiracies” in order to frame anarchists. To date, all of these efforts have been embarrassing failures. Now, the Russian secret police have introduced an innovation: by kidnapping anarchists without warning, planting weapons in their cars, and torturing them until they agree to sign forged “confessions,” they hope to finally make charges of participating in a “terrorism network” stick. If they succeed, we can expect to see other police agencies across the world emulate their tactics.

In the following analysis, we will review the history of this model of repression, explore the details of the Russian torture cases, and outline how we can respond. The Appendix lists the details of the arrests and torture in chronological order and provides corroborating evidence of the reports herein.

We’ve also prepared posters expressing solidarity with those targeted in this wave of repression. Please print them out and paste them up to draw attention to this case.

Then the man in gloves cranked the dynamo. The current flowed to my knees. My calf muscles contracted, and I was seized by paralytic pain. I screamed. My back and head convulsed against the wall. They put a jacket between my naked body and the stone wall. This went on for about ten seconds, but when it was happening, it felt like an eternity to me.

One of them spoke to me.

“I don’t know the word ‘no.’ I don’t remember it. You should forget it. You got me?” he said literally.

“Yes,” I replied.

“That’s the right answer. Attaboy, Dimochka,” he said.

The gauze was stuck in my mouth again, and I was shocked four times, three seconds each time. […] Then I was tossed onto the floor. Since one of my legs was tied to the foot of the bench, when I fell, I seriously banged up my knees, which bled profusely. My shorts were pulled off. I was lying on my stomach. They tried to attach the wires to my genitals. I screamed and asked them to stop brutalizing me.

“You’re the leader,” they repeated.

“Yes, I’m the leader,” I said to make them stop torturing me.

“You planned terrorist attacks.”

“Yes, we planned terrorist attacks,” I would reply.

One of the men who measured my pulse put his balaclava on me so I would not see them. At one point, I lost consciousness for awhile. […] After they left, a Federal Penitentiary Service officer entered the room and told me to get dressed. He took me back to my solitary confinement cell.

The next day, October 20, 2018, I broke the tank on the toilet and used the shards to slash my arms at the wrists and elbows, and my neck in order to stop the torture. There was a lot of blood from the cuts on my clothes and the floor, and I collapsed onto the floor. They probably saw what I did via the CCTV camera installed in the cell. Prison staffers entered my cell and gave me first aid. Then the prison’s psychologist, Vera Vladimirovna, paid me a visit.

From the transcript of attorney Oleg Zaitsev’s interview with arrestee Dmitry Pchelintsev about his experience of torture in FSB custody

A Brief Summary of the Cases: Lies, Forgery, and Torture

The story begins in Penza in October 2017, when the FSB arrested six anti-fascists who sometimes played airsoft. According to the FSB, all the detainees were members of the unimaginatively titled organization “Set” (“Network”) and were planning to use bombs to “destabilize the political climate in the country” during the presidential elections and the FIFA World Cup. They alleged that the network’s cells were operating in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Penza, and Belarus.

FSB officers planted weapons and explosives in the vehicles of some arrestees and tortured them in the pre-trial detention center, beating them, hanging them upside down, connecting electrodes to their bodies with which they electrocuted them, and threatening them with even worse. Using these methods, the officers forced the arrestees to agree to validate forged testimony professing that they are part of the alleged terrorist “Network.” At the end of January 2018, two more antifascists were arrested in St. Petersburg. They were also beaten, tortured by means of electrical shock, and forced to agree that they too were members of the invented “Network.”

As of now, seven anti-fascists are behind bars and another is under house arrest, facing up to a decade in prison.

After news spread about the arrests and torture, activists organized solidarity actions in Russia and elsewhere around the world. The Russian state responded with additional crackdowns. In Moscow, officials detained participants in solidarity actions and pressed criminal charges against them. Anti-fascists from Chelyabinsk were detained, tortured with electric shocks, and now face charges as well.

On March 21, the FSB admitted to inflicting electrical shocks on at least one of the arrestees. Members of the public supervisory commission of St. Petersburg had visited defendant Viktor Filinkova a few days his arrest and recorded dozens of marks from electrical torture on his body. The FSB acknowledges that officers inflicted these injuries on Filinkova via electrical shock attacks, but maintain that this was necessary “to prevent him from escaping.”

The appendix, below, includes a chronological list of the arrestees, including excerpts from their accounts and accounts from lawyers.

Previous Precedents in Europe and the US

One of the first contemporary attempts to fabricate a far-reaching criminal conspiracy in order to frame anarchists took place in Italy in the mid-1990s, in what became known as the Marini trial. As one of the birthplaces of the original anarchist movement, Italy has always been ahead of the curve when it comes to strategies of repression. It’s worth quoting at length from the analysis of the Marini trial that anarchists published at the time, as it offered an ominous portent of everything that has followed in the years since:

“With the so-called Marini trial, they have taken a more sophisticated approach. They have invented a fictional criminal anarchist organization with two tiers: the larger aboveground tier consisting of publications, presses, occupied centers and so on; and the clandestine portion, the armed gang. Using this fictional construction, state prosecutor Antonio Marini charged dozens of anarchists with “subversive association” and “armed gang” (and a few with crimes related to actual events). The only evidence for the “subversive association” and “armed gang” charges are the letters, periodicals, e-mails, conversations, and visits among those charged.

“Because these charges (particularly that of “subversive association”) are, in fact, not very defined, they give the state a sword to go on holding over anarchists’ heads. If one trial fails, new investigations can be opened, and the Italian authorities keep on opening investigations involving raids, searches, bugging, harassment—all the usual police tactics. Even if the number of convictions that these charges succeed in bringing about is low, this process can easily lead comrades to focusing their energy on self-defense rather than attack against the social order. When this occurs, the strategy of the state has been successful.”

In 2008 and 2009, police carried out raids with the intention of establishing the existence of nationwide anarchist terror networks in France (the “Tarnac 9” case) and the United States. Neither of these efforts ultimately succeeded.

In an article we published in 2010, “The Age of Conspiracy Charges,” we reviewed over a dozen high-profile political conspiracy cases initiated in the US between 2004 and 2010 targeting anarchists and their associates. Several of these efforts sent people to prison for years or decades, but none of them succeeded in demonstrating any evidence of worldwide or nationwide terror networks.

After the high-water mark of popular struggles in 2011, police around Europe counterattacked with another wave of attempts to invent anarchist terror networks. In late 2014 and early 2015, police in Spain and Catalunya carried out Operations Pandora and Piñata, arresting dozens of anarchists and charging many of them with being part of a terrorist group—on the basis of evidence such as their having co-published a book entitled Against Democracy. By the beginning of 2018, this attempt, too, had proved to be a dismal failure. An important factor in the defeat of this wave of repression was the broad support the defendants received throughout the Iberian peninsula, including a solidarity campaign on the theme #YoTambienSoyAnarquista (“I too am an anarchist”).

Police in Czech Republic imitated the Spanish example, initiating their own Operation Fenix in April 2015. This also did not turn out well for the authorities, with the trial ending with all defendants acquitted and the state scrambling to invent new justifications to continue harassing its targets. Thanks to strenuous solidarity efforts and the laziness, incompetence, and stupidity of the police, the authorities failed to convince even their own reactionary legal officials that these fake terror networks existed.

For more background on repression throughout Europe during this period, read “On Repression Patterns in Europe,” which offers a critical overview of repression and solidarity in six countries.

Seeking to improve on all these failures, in 2017, the Russian security services introduced an innovation: using horrific methods of torture, they set out to terrorize arrestees into signing statements proclaiming their guilt themselves. Thus far, they have succeeded in forcing a half dozen people to acknowledge membership in a far-fetched “terror network” that had not actually carried out any actions.

Why the Russian Model Could Spread

The police of all nations are interlinked in a global network. They exchange tactics, strategies, and training; innovations in one field or region are swiftly passed on to others. It is plain for all to see that governments and the models of policing that they employ have become increasingly authoritarian since the turn of the century. In this context, it’s no stretch to imagine that police in Europe and the US might emulate the Russian model for concocting a conspiracy and forcing their targets to confirm its existence by means of torture.

Does this really seem hard to imagine?

The authorities in Europe and the US are certainly not above fabricating excuses to press charges. As we outlined in Bounty Hunters and Child Predators, the police are often too lazy to target actual anarchist organizing. Bringing the negligence of all cynical employees to their work, they frequently find it easier to entrap inexperienced individuals who are peripheral to anarchist movements. In the US, this is adequately illustrated by the entrapments of Eric McDavid, David McKay, Bradley Crowder, Matthew DePalma, the NATO 3, and the Cleveland 4, to name just a few examples, by FBI agents provocateurs like Andrew Darst and Brandon Darby. None of these people would have engaged in illegal activity had it not been for pressure and, in some cases, outright seduction from FBI operatives. All of them served years in prison as a result. Eric McDavid’s conviction was overturned nine years into his 19.5-year sentence when it came out that the FBI had concealed evidence that exonerated him; but in all of these cases, the authorities used roughly the same approach.

It is well documented that the US has employed torture against US and European citizens, including tactics such as beatings, forced anal penetration, forced drug injections, denial of food and water, exposure to extreme cold, and threats of imminent death. A report by the Justice Department Office of the Inspector General acknowledged that after 9/11, detainees were slammed face first into a wall against a shirt with an American flag; the bloodstain left behind was described by one officer as the print of bloody noses and a mouth. US military interrogators have committed suicide as a consequence of their role in torturing detainees.

There are also reports of US government interrogators using electrical shocks and mock executions being used to force them to sign forged “confessions.” This is the FSB model.

Nor is it unrealistic to imagine that police in Europe or the United States would use torture against anarchists. Italian police tortured arrestees during the 2001 G8 summit in Genoa, as the European Court of Human Rights recently acknowledged. There were reports of police torturing arrestees during protests against the 2003 Ministerial planning the Free Trade Area of the Americas in Miami. Since then, various city governments have paid out countless millions of dollars as a consequence of police misconduct; it takes a long time to get external confirmation of torture, but over the coming years, we will surely see many more cases from the past fifteen years come to light.

The current US administration is outright eager to see torture employed more widely. Just as the agenda of the Trump administration has been a driving force in unprecedented new crackdowns such as the J20 prosecutions, it is realistic to expect that the enthusiasm Trump and his cronies have shown for Russian “toughness” will be reflected in the activities of police and federal agents in the years to come.

By the time the authorities get around to trying out new strategies on anarchists, we can be sure they will already have employed them against Muslims and poor people of color. This is yet another reason for us to engage in solidarity organizing with communities more targeted than our own, so we can keep abreast of police tactics that are likely to be employed against us next.

Previous Precedents in Russia

The tactic of forcing defendants to validate false testimony is not new to Russia, as a cursory review of the history of the USSR will show. Likewise, this is not the first time that the Russian security services have attempted to frame anarchists and anti-fascists by means of a concocted terror conspiracy.

For example, during the year before the presidential elections of 2012, the Nizhny Novgorod Counter-Extremism department concocted the so-called Antifa-RASH case, in which they accused several anti-fascists of laying the groundwork for an armed coup; they even fabricated blatantly false “membership cards,” which were riddled with errors. Three of the defendants were eventually amnestied, but two remain in exile to this day.

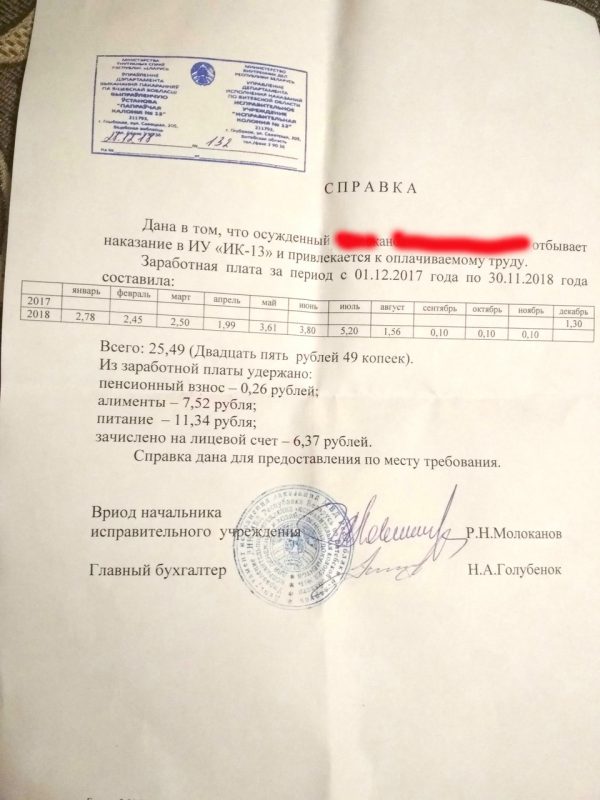

Obviously fake “membership card” fabricated by the Nizhny Novgorod Counter-Extremism department to entrap anti-fascists in 2011.

After the parliamentary elections at the end of 2011, massive protests broke out in Russia and continued through the presidential elections. Apparently, this popular reaction struck fear into the Russian government. When Putin returned to power, new repressive legislation was introduced in order to systematically suppress all protest movements and criticism of the government.

Until 2014, the authorities had cooperated with far-right nationalists. But after the Maidan uprising in the Ukraine, they cracked down on nationalists and fascists as well. And after the annexation of Crimea, the authorities brought more and more criminal cases against so-called terrorists and extremists: against Moslem people from “non-traditional” denominations, against Crimean Tatars, against nationalists, anarchists, and anti-fascists. For example, in the case of Sentsov and Kolchenko, an anarchist was sentenced to ten years imprisonment alongside an accused member of the Ukrainian fascist party Right Sector—despite his only connection to nationalists being that he had been beaten by them.

For some years, the nationalist Vyacheslav Maltsev promoted the idea that there would be a revolution on November 5, 2017. Maltsev himself left Russia due to a criminal charge against him (“Public calls for extremist activity”). Starting in October 2017, the authorities arrested many people connected to Maltsev and his movement throughout Russia and accused them of preparing terrorist attacks.

This is how it came to pass that, in the city of Penza, antifascists who had an airsoft team called “5.11”1 were arrested, tortured, and accused of terrorism. When the secret service understood that the arrestees had nothing to do with nationalist revolution, they fabricated a conspiracy charge: participation in an invented anarchist terrorist group, “Network.” Thus the FSB sought to smash both right-wing and left-wing movements at the same time.

All this took place in advance of a new round of presidential “elections” on March 18. Putin and his colleagues wanted these elections to occur without protests afterwards. That’s why they set out to intimidate everyone who could potentially bring people into the streets.

Meanwhile, Russia is preparing to host the FIFA World Cup. As we documented in reference to the World Cup in Brazil, mega-projects like the World Cup offer oppressive state governments the opportunity to carry out massive new initiatives of restructuring and repression. The Russian Secret Services were determined to show that they could effectively prevent terror attacks—and the easiest way to do so was to invent a threat. This is another factor that explains the new wave of repression against anarchists and antifascists in Russia.

The fact that the state intensified its attacks against anarchists and anti-fascists after finally cracking down on far-right groups should serve as a reminder that anti-fascists should be careful, in the course of their organizing, not to legitimize any form of state repression, even against the most dangerous fascists. Whatever the state does to fascists today, it will surely do to anarchists and other rebels tomorrow.

What We Can Do

What can we do to support the Russian defendants and thwart the attempt to innovate a new model for repression?

At the very least, we have to direct attention to the Russian torture cases in order to discredit the Russian police, in hopes of discouraging the security services of other nations from following their example. This much should be possible. Only a few years ago, Pussy Riot became darlings of the liberal media, filling the time-honored role of “Russian dissidents.” At a time when Donald Trump’s collusion with Russia dominates the news, it should be possible for us to use the same channels that publicized the J20 cases to draw attention to these cases too.

In responding to fabricated conspiracy cases, we can draw on our previously mentioned text, The Age of Conspiracy Charges:

1. Don’t let the state intimidate us out of confrontational public organizing.

The state targets public organizers because they are effective. Even when it is framed as a strategic choice, retreating from public organizing can only play into the hands of the authorities. Repression is intended to cause militants to back away from engaging with the public, losing connection with a broader social base and deepening the false dichotomy between passive “community organizing” and clandestine direct action. This is not to say everyone must organize publicly—on the contrary, one function of public organizing is to prepare a favorable ground for more generalized and anonymous actions—but that it is a necessary aspect of anarchist struggle.

2. Minimize our vulnerability to conspiracy charges.

There are many ways we can do this. Perhaps the most obvious is to practice appropriate security culture, sharing sensitive information on a need-to-know basis and doing our best to keep informants out of our circles. Security culture is not only for those who may be party to illegal activity; it is important for everyone connected to networks that the state is interested in mapping or disrupting.

Likewise, it’s important to keep an eye out for federal bounty hunters preying on naïve young activists. Often they prefer to target the least experienced or connected individuals in a social milieu instead of tangling with longtime militants. We can also inoculate ourselves against disruption by sorting out internal conflicts before they offer infiltrators or prosecutors opportunities to divide us against each other.

Whenever someone is targeted with a politically motivated conspiracy case, it’s important that we mobilize the very best legal defense we can. Every conspiracy case against radicals sets a precedent for more of the same; defending one of us is literally defending all of us. Good lawyers serve two functions. First, they intimidate the state, which will be more likely to bargain or drop charges if it knows pressing them will be expensive and risky. Second, they can win cases or get them thrown out. Raising the money to defend one person effectively can save a lot more money and heartache in the long run.

Public support campaigns are equally important. On one side, this means going public when you are targeted—both so you can receive support and so that repression will be brought into the spotlight. On the other, it means organizing long-term support for defendants, so they will feel invested in answering to the community and so the authorities will have to factor in public relations challenges when they consider whether to target us. Support campaigns can target the most vulnerable individuals in the power structure; the supporters of the RNC 8 did this by concentrating on county attorney Susan Gaertner, who was eventually forced to drop the terrorism charges against the defendants.

Finally, though this should go without saying, we can protect ourselves from conspiracy charges simply by not cooperating with the authorities. Many of these cases would never have gotten off the ground if people had not been intimidated into making statements against their former comrades. Nobody talks, everybody walks—that goes for our whole community as well as specific groups of defendants.

Defendants who cooperate with the government never come out ahead. As detailed below and elsewhere, not only do they lose friends and community support, they rarely get significantly shorter sentences—and doing prison time is much harder as an informant.

3. Craft an effective narrative discrediting the state’s use of conspiracy charges and circulate it to the general public.

If the authorities come to rely on pressing conspiracy charges against anarchists as a central strategy of repression, we must take advantage of the ways this makes them vulnerable. Many in our society—and not just radicals—are uncomfortable with the idea of people being persecuted for thought crime. We need to find ways to address people outside our social and political circles about the prevalence of conspiracy charges, so as to utilize this opportunity to discredit the state and delegitimize conspiracy-based cases. The broader the range of people who disapprove of this tactic, the more the hands of the authorities will be tied. Most of this work has yet to be done. If you are concerned about government repression, consider the ways you can approach others outside radical communities about this issue.

When we talk about conspiracy charges and witch hunts, it’s important to emphasize that we’re talking about the state, which exists to carry out violent repression. As long as there are inequalities and injustices, there will be resistance, and those in power will attempt to repress it. If we take ourselves seriously as a revolutionary movement, we need to see ourselves in the larger context and histories of resistance movements and the repression they have faced; we would do well to learn both from the successes and the failures of the past. It’s also important to remember that repression is a daily fact of life for countless people in communities on the wrong end of power and privilege; anarchists are far from exceptional in this regard.

Obviously, it is much more difficult for people to resist the pressure to cooperate with the authorities—and even to agree to validate outright lies—when they are grievously tortured. This makes solidarity and publicity efforts all the more important in this context.

To donate money to support the legal defense of the arrestees, you can use Paypal to send funds to the Moscow Anarchist Black Cross at abc-msk@riseup.net. Add a note that the funds are for “St. Petersburg and Penza.” Send euros or US dollars.

Here are some other ways to donate:

- Yandex (wallet of the Anarchist Black Cross St. Petersburg) :

41001160378989 - Bitcoin :

1EKGZT2iMjNKHz8oVt7svXpUdcPAXkRBAH - Litecoin :

LNZK1uyER7Kz9nmiL6mbm9AzDM5Z6CNxVu - Etherium :

0x1deb54058a69fcc443db2bf9562df61f974b16f7 - Monero :

4BrL51JCc9NGQ71kWhnYoDRffsDZy7m1HUU7MRU4nUMXAHNFBEJhkTZV9HdaL4gfuNBxLPc3BeMkLGaPbF5vWtANQn4wNWChXhQ8vao8MA - Zcash :

t1dX9Rpupi77erqEbdef3T353pvfTp9SAt1

If you need another option for transferring money, contact the Anarchist Black Cross of Moscow: abc-msk@riseup.net

Soirce: https://itsgoingdown.org/why-the-torture-cases-of-anarchists-in-russia-matters/