Many Belarusians are often perplexed by the slow pace of European Union sanctions against Lukashenko. The responsibility for the delay lies with Putin and his entourage, who for years have been developing networks of influence in the EU countries. It is the pro-Russian parties that are stalling any sanctions not only against Putin, but also his friends around the world.

Corruption does not exist only in authoritarian countries. It also exists in representative democracies. For example, it recently became known that former Austrian Foreign Minister Karin Kneissl has been appointed to the Rosneft board of directors. The exact sum of her loyalty to Moscow is unknown, but in the same position former Chancellor of Germany and socialist with a taste for blood money Gerhard Schroeder earned $600,000 per year. Karin Kneissl became minister as a result of a coalition between the Austrian center-right and the far-right FPÖ. To be fair, Kneissl did not defect to Putin’s camp in a matter of days. In 2018, the friendship between the foreign minister and the Russian tyrant peaked when Kneissl invited Putin to her wedding in Austria. After the collapse of the coalition, the politician wrote periodically in Russia Today.

The coalition with the ultra-right in Austria collapsed because of the scandal surrounding the vice-chancellor, who met with representatives of a Russian oligarch in Ibiza. During the meeting, they talked about state contracts in favor of a Russian firm. As a favor to his campaign. A video of the meeting leaked onto the internet, the government fell apart, and new elections were held in Austria.

The far-right political parties in the EU are generally loyal to Putin. Remember, for example, the story of the so-called Crimean referendum – the OSCE refused to be present during the political farce. Instead, politicians from parties like Alternative for Germany, the National Front from France, and many others went to occupied Crimea to create legitimacy for Putin’s annexation.

Although many pro-Putin parties remain marginal, some of them represent quite a serious political force. For example, the candidate of the far-right Rassemblement Nationale (formerly Front Nationale) has a very real chance of becoming the new president of France. In Italy, the fascists of the “Italian Brotherhood” party and the far-right “Lega” (formerly “Lega Nord”) are very likely to win the next elections. Both parties hold pro-Russian positions:

“The goal of the Italian Brotherhood in government will be to revise Italian foreign policy, with the restoration of strong relations with Russia in terms of economic and security partnership as a priority. I do not think Russia is an enemy of Europe or the West. On the contrary, I believe that Moscow can play a fundamental role as a balancing force in the world and as a link [of the West] to the geopolitical space called Eurasia,” the president of the Italian Brotherhood said in a 2018 interview.

Putin also finds allies in the EU among the authoritarian left. Parties such as Germany’s Left or Greece’s Syriza very often take pro-Russian positions in local and European parliaments. No corruption scandals have yet emerged around such support, but EU politicians are unlikely to help Russia for free.

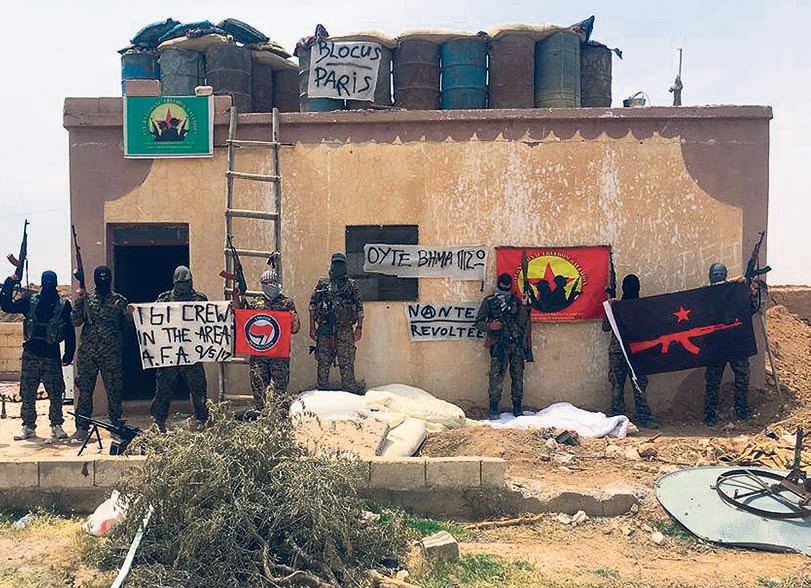

For the European far-right, Putin is an excellent example of a strong conservative power capable of keeping liberals, socialists, and the self-organized part of society in check. Fascists love fascist regimes in other countries. The authoritarian left sees Putin as a hero, fighting Western imperialism, standing up for the people.

All these ultra-right and authoritarian leftists are ready, if necessary, not only to take a pro-Russian position, but also to help regimes such as Lukashenko’s. These political forces have played no small role in torpedoing any economic sanctions against the Belarusian regime for many years.