We are a working group of anarcho-feminists who initiated a transformative process regarding the situation with Mikola Dziadok. We have decided to publish this report to describe the progress of our work, the mistakes we made, and our conclusions. We are doing this for two reasons:

- We believe this experience is important and useful for the development of the non-carceral feminist and anarchist movement, and we want to share it so that others can use this knowledge to work with cases of violence in their communities.

- We want to maintain a culture of accountability and recognition of our mistakes, so we also want to openly talk about the mistakes that we believe our group made during the process.

Important caveats:

- This text is not a detailed analysis of Mikola’s actions. In our work, we proceeded from the assumption that Mikola is responsible for entering into an unequal relationship with a girl much younger than him and causing her harm.

- This text is not a call to cancel Mikola. Our group was created on an ad hoc basis to carry out this process and does not have the authority to cancel anyone. We believe that the collectives and individual participants of the movement are capable of independently drawing conclusions about how they will interact further with Mikola after reading the report.

- This text is not a theoretical guide. If you are unfamiliar with the concepts of transformative justice and non-carceral feminism, we recommend referring to the list of references at the end of the report.

A brief overview of the principles of transformative justice

The transformative approach is part of a general non-carceral approach to creating safety and eliminating violence in society. This means that within this approach, we do not use punishment as the primary tool for ensuring safety.

As anarchists, we do not believe that social isolation and the prison system make society safer. We are convinced that safety is achieved through changing social norms, taking responsibility for these changes, and the internal work of community members.

The transformative approach involves working with perpetrators of violence to help them understand the reasons for their actions, take responsibility, and change their behavior.

Forming a working group and starting the process

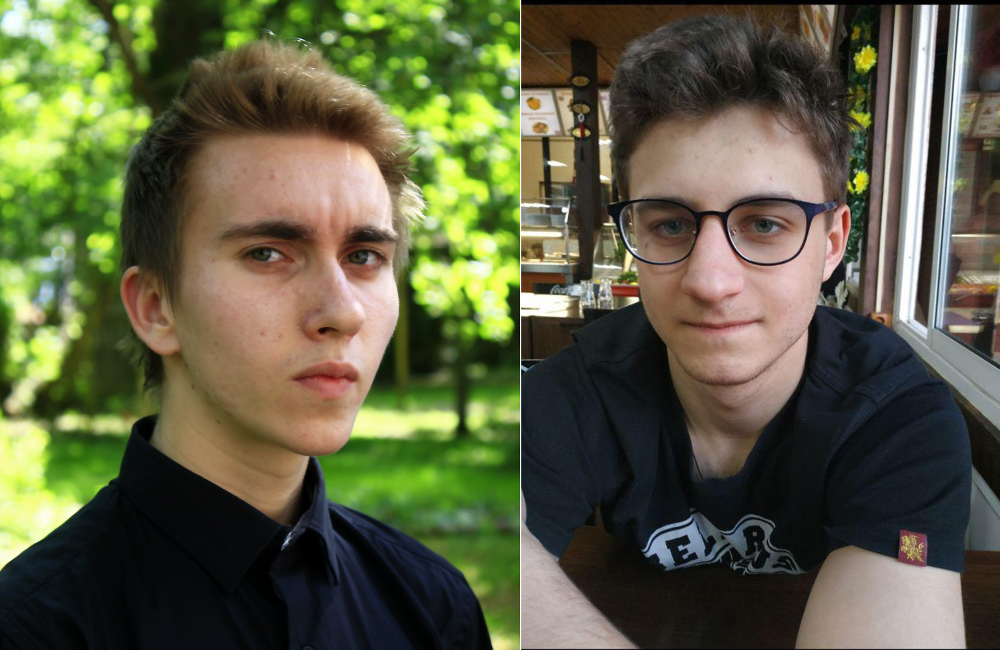

After Mikola’s release, Comrade A began receiving messages with Telegram channel posts from a girl who he was in a relationship with in 2017 when she was 16 and he was 29. The posts described a relationship where Mikola was emotionally abusive, coerced the girl into sex, insisted in unprotected sex yet was firmly anti-abortion.

Many anarchists in the movement knew about Mikola’s relationship with the 16-year-old girl, but at the time did not question it (at least in personal communication with him). No one in the movement knew (or realized) that there was violence in their relationship; this only became known after the victim’s posts.

The situation caused a stir. Most comrades condemned Mykola’s actions. A working group was formed to initiate a transformative process. Within the group, comrade A took on the task of communicating with Mykola, while comrade B communicated with the girl who received harm.

Communication with Mykola

In the first conversation, comrade A showed Mykola the girls’s posts. He did not go on the defensive, did not deny the relationship, and seemed upset. We felt that he was open to dialogue.

Based on this reaction, we decided that working with him was possible: we planned to help Mikola analyze his past actions, assess his changes, and develop strategies for nonviolent behavior.

Communication with the victim

Comrade B contacted the girl, explained the essence of the process, and asked how we could support her.

The girl was surprised and frightened by the movement’s attention to this case. As a measure of support, she asked for compensation for the cost of therapy.

Request for silence

In a chat room for feminist activists, we asked the feminist community to refrain from discussing the case publicly (on social media or in the media) for two months. We were concerned that if a public discussion unfolded around Mykola, he would become defensive, want to respond quickly, and not have time to reflect on his behavior and take responsibility for it.

We wanted to give him time to work on himself internally without external pressure. The victim was notified of this request; we made it clear that if she needed publicity, we would be guided by her wishes.

Challenges and external factors

Our process was complicated by a number of circumstances:

- Lack of experience in conducting transformative processes. Our group had mainly theoretical knowledge about how to conduct such processes.

- The status of the person who caused harm. Mikola is a public figure with significant social capital.

- Mikola’s psychological state — he had just been released from prison after five years of torture and was in a difficult emotional state.

- Distance from the victim. The victim is not part of the anarchist movement, and none of us or our comrades had a close relationship or the trust necessary to provide support and safe communication in such a painful situation.

- Fragmentation of the anarchist movement. Due to emigration, connections have weakened, and collective work and communication have become difficult.

- Remote format. The work was carried out exclusively through phone calls, as we did not have the opportunity to meet with Mikola in person.

- Gender imbalance. Initially, it was planned that Mikola’s support group would include comrade A and a man from the movement. But Mikola did not want to talk about this situation with men, so comrade A was the only one who communicated with him on this topic during the process.

- External aggression. Mikola’s circle (people who were not part of the anarchist movement and did not share our values) harassed the victim online and spread her personal information, which exacerbated the situation.

Working with Mikola

For two months, Comrade A had conversations with Mikola, trying not to criticize him directly, but to ask leading questions. We saw that he was not ready to take responsibility for the harm he had caused, but he showed a willingness to reflect. For example, he acknowledged that such an age difference was unacceptable.

Other comrades (including comrades from our group) also communicated with Mikola. Mikola listened to the arguments and agreed that his and the victim’s perceptions of the events might differ, but he vehemently denied the allegations of violence.

The issue of compensation:

The group discussed the victim’s request for payment for therapy. According to the principles of transformative justice, the person who caused the harm must try to compensate for it in accordance with the victim’s requirements. But compensation for harm only occurs after the person realizes the harm they have caused and takes responsibility for it. We were concerned that early payment would be perceived by Mikola as a “payoff” and he would consider the process complete. But we understood that it could take a long time to reach this stage.

In the end, Comrade A mentioned the money in a conversation with Mikola. He flatly refused to pay, citing the fact that he had provided financial support to the girl in the past during their relationships and felt used.

Work within the movement:

Within the anarchist movement, we also worked to change our community:

- We organized discussions in our collectives about adult-teenager relationships.

- We organized a conference call for girls in the movement to discuss how free and safe anarchists feel in the Belarusian movement.

- We planned a general conference call with the movement on the situation with Mikola.

The Facebook post incident

Mikola was under pressure because of the victim’s posts and wanted to speak out publicly. Comrade A, without consulting the group, supported the idea of writing a post. Comrade A informed Comrade B that Mikola was preparing a post, but the rest of the group did not know about it.

Our mistake: The group found out about the upcoming post after the fact. Most importantly, we forgot to warn the victim. We take responsibility for this mistake and have apologized to the girl.

Here’s the post in question – you can use autotranslation to read it https://www.facebook.com/happymikola/posts/pfbid02mtNhDX6T7zMATUXhvehQ11Wj3HuEHA8CPnr1o4r4ZkagPRWqiVbC8kmrq2HuaXNXl

The post that was published was bad. Mikola did not take responsibility for the harm caused, only acknowledging the age difference (“I admit my responsibility for everything that happened and for my choice in the past”). Nevertheless, we saw this as at least some step forward.

In response to the public criticism that followed the post, Mikola went on the defensive, began to see the “hand of the secret services” in the actions of his critics, liked insults directed at the victim, accused her of lying in interviews, and collected compromising information on her.

The crisis of the process and the final call

Shortly after the post was published, we realized that Mikola did not understand the essence of the transformative process. In a conversation with his comrades, he heard the term “justice” and became angry, perceiving the process as analogous to a court trial. He began to appeal to the presumption of innocence and statutes of limitations, concepts that have no place in transformative justice. This was the result of our mistake: we did not explain the essence of the process clearly enough at the start, fearing that we would scare him away.

We held a group conference call with Mikola to clarify the situation. Mikola’s position during the call was as follows:

- Denial of the problematic nature of unequal relationships. He acknowledges the fact of inequality but does not see it as a problem. He considers himself the aggrieved party in a “mutually toxic” relationship.

- Refusal to discuss. Mykola categorically refused to comment on specific episodes from the victim’s posts, calling it “immoral digging through dirty laundry.”

- A feeling of betrayal. He perceived the very fact that the movement trusted the victim’s words as a betrayal. He accused the group of bias.

Mikola did not see the difference between a transformative process and a punitive trial. Our attempts to explain that we do not consider him a “rapist” or a “pedophile,” but want to examine patterns of unequal relationships, fell on deaf ears.

In the end, we saw that Mikola was not ready to take responsibility for the harm he had caused in his relationship with the victim. At the end of the call, he refused to continue participating in the process and withdrew from it.

Analysis of mistakes

We believe that we made a number of critical mistakes during the process:

- Poor communication with the victim. Long pauses in communication and the lack of warning about Mikola’s post caused her additional harm.

- A vague start. We did not explain to Mikola immediately and clearly what the transformative process was, saying only that the movement was very concerned and interested in him speaking about it. As a result, he perceived the process as “solving problems with damage to his reputation” rather than working on himself.

- We weren’t firm enough. Afraid of scaring Mikola away, we avoided direct criticism at the beginning, which gave him a false sense of support for his position.

- Insufficient involvement of the movement. We did not write regular updates for our comrades about how the process was going, mainly conveying information about it in private conversations.

- Internal communication problems. We did not involve all members of our group equally in the process. Often, only comrades A and B exchanged urgent information, while the rest of the group found out about it later.

- Disbalanced communication with Mikola. We followed Mikola’s wishes and did not appoint a man from our group to communicate with him during the process alongside Comrade A.

Conclusion

Despite Mikola leaving the process and us making mistakes, we remain convinced that a transformative approach is the best way to deal with violence within the movement.

We want to emphasize that Mikola’s departure from the process does not mean our work is done. We continue our work within the movement to not only respond to incidents, but also to prevent them.

We hope that our experience and this report will be useful to everyone.

If you have any questions about how the process went, you can ask them by email at transformativeprocessgroup@proton.me.

List of sources:

- Creative Interventions Toolkit (English) — A textbook on community-based justice (https://www.creative-interventions.org/toolkit/)

- Zine on how to conduct transformative processes La Cinetika: Commission on Gender (English) — The experience of a transformative justice collective with six years of practice (https://lacinetika.wordpress.com/comissio-de-genere/)

- Accounting for Ourselves (English) — An essay on the reasons for the failure of transformative processes. (https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/crimethinc-pfm-accounting-for-ourselves)

Szacunek dla Was za inicjatywę i inspirację. “Anarchistyczne sądy” są nam bardzo potrzebne i szacunek za taka próbę.

Ciekawy wątek, że Mikola nie mógł pzestawić w głowie myślenia z państwowych sądów i ich prawa, na taką formę podejścia do tematu. To daje dużo do myślenia i sugeruje, że wielu z nas może tak mieć.

Pewnie tak jest. Dzięki takim inicjatywom, łatwiej o tym rozmawiać.

Dzięki i pozdrawiam z zachodu.